A recent report by the Office for Students (“OfS”) reveals some interesting insights into the challenges still faced by disabled students in university education. Whilst the report acknowledges that notable progress has been made, it argues colleges and universities still need to do more to ensure disabled undergraduates and post-graduates enjoy just as full a student experience as their non-disabled peers. At its core, the report highlights the need for all further education providers to adopt the ‘social model of disability’. It is this fundamental change in attitude and behaviour that will ultimately remove barriers for disabled people and pave the way for true inclusivity. But how far have providers gone to accept this model and what are the barriers which still hinder disabled students from fulfilling their true potential?

Education, education, education!

Education is invaluable in breaking down barriers. It brings about increased mobility and social justice. Unfettered access to it is crucial in ensuring a fair society. No matter what background, religion, colour or ethnicity, everyone has the right to a fair and inclusive education system. The same must be said for disabled students.

The OfS is an independent regulatory body of the Department of Education. It was established in 2018 and acts as a regulator of the higher education sector in England. According to its report released in October 2019, disabled students now make up 13.2% of undergraduates and post-graduates attending college or university. This is a welcome increase compared to 8.1% in 2010.

Disabled students have a valuable contribution to make in a tutorial discussion or seminar room. They bring a broader spectrum of views, experiences and perspectives whilst also generally enriching the student body outside the lecture theatre. However, the OfS insight paper reveals that disabled students are still less likely to continue their degrees, graduate with a good degree and progress onto a highly skilled job or further study than their non-disabled counterparts.

The social model of disability

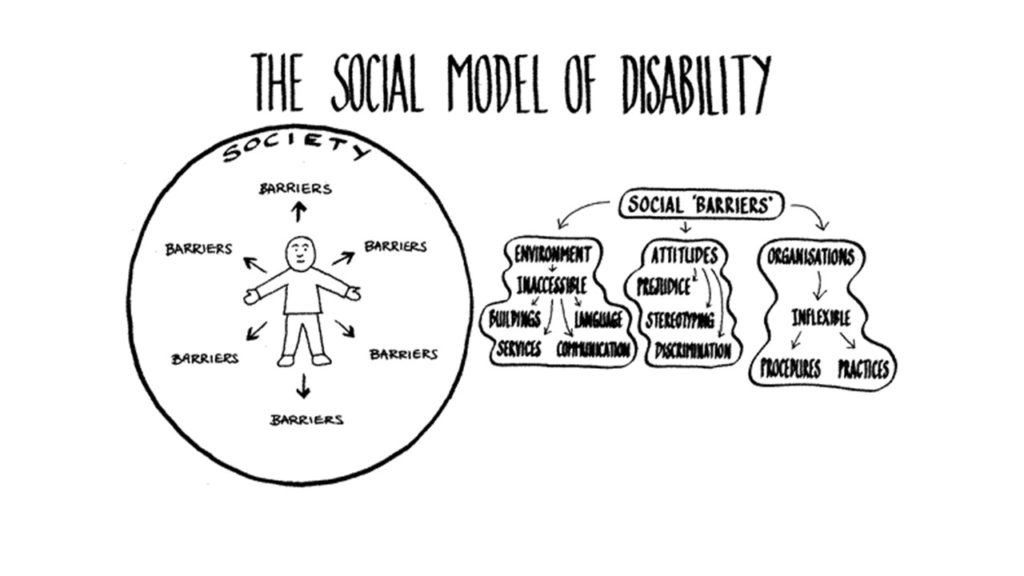

One of the fundamental tenets of the OfS insight report is the need for further education providers to fully adopt the ‘social model of disability’. This model is rooted in the understanding that disability is not the problem of the individual disabled person which needs to be ‘fixed’. The approach is more about engendering a fundamental change in attitude towards disability to create an environment where barriers to disabled people are removed and everyone can flourish.

To put it another way, genuine inclusivity for disabled students is not achieved by addressing each individual and their disability on a case by case basis through a system of adopting ‘reasonable adjustments’. Rather, the goal is to encourage a more proactive approach in providing a supportive culture where the needs of all disabled students can be met holistically.

The OfS recognises that whilst great strides have been made by further education providers in moving towards the social model, notable gaps persist. According to the report, the true adoption of this approach remains aspirational.

A statutory and regulatory push towards inclusivity

Acts of Parliament

Much has been done by the legislature to entrench the rights of UK disabled citizens in the statute book. The Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (“DDA 1995”) made it unlawful to discriminate against people in respect of their disabilities in relation to employment and the provision of goods and services. The Special Educational Needs and Disability Act 2001 brought educational organisations within the remit of the DDA and made it necessary for these institutions to make “reasonable adjustments” for disabled students. More recently, the Equality Act 2010 legislated to force universities and colleges to ensure equality of opportunity for disabled students by: changing rules or practices; altering or removing physical barriers; and providing support services or devices.

OfS and Disabled Students’ Commission (DSC)

In 2018, the OfS merged the responsibilities of the Higher Education Funding Council for England and the Office for Fair Access. It has various significant powers, notably administering a budget of £40m to universities across England to help create an inclusive environment for disabled students.

The OfS has also set up the centre for Transforming Access and Student Outcomes (“TASO”). TASO operates as an independent hub to provide leading research and toolkits as well as best practice models to help higher education providers provide the most inclusive student experience possible.

As well as the OfS, the DSC was established in 2019 as an independent and strategic group designed to advise higher education providers on how best to improve support for disabled students.

The creation of these two organisations is significant. In order to be able to charge the full levy of undergraduate student fees, for English and Welsh students, which currently stands at £9,250 per year, universities must submit access and participation plans to the OfS which identify the different outcomes that different groups of students experience. These plans can be monitored and the OFS can take action when universities fall short.

Though this mix of regulatory pressure, targeted funding and sharing of effective practice, the intension is to encourage universities to bring about positive change for disabled students.

Three key challenges

However, the journey towards full inclusivity is a slow one. Despite the increase in students declaring themselves as disabled, brought about by changes in law, increasing acceptance and reforms at school level, there are many real obstacles which hinder disabled students’ full integration with the student body.

- Decrease in funding

One of the main obstacles facing disabled students is the noticeable decline in funding available through the Disability Student Allowance (“DSA”). In 2015 a change to the criteria for Disability Student Allowance, meant that non-medical assistance is no longer covered. Students are now also required to pay the first £200 towards assistive technology.

Such changes to the DSA, make the need for universities to truly adopt the ‘disability social model’ ever more pressing. Indeed, the OfS has £40m at its disposal to help universities transform their campuses into more inclusive environments. The hope is disabled students will no longer have to rely on individual funding by the DSA. Instead, the resources and facilities already on offer to them at further education providers will help to incorporate them fully into the student body.

Instances of such resources might be different types of seating or lighting provided in student libraries such as at Warwick University. Another example might be the widespread use of lecture capture. At Huddersfield University, automatic video recording of all lectures is standard practice except where specifically requested by tutors.

- Providing support at all stages of the student lifecycle

Disability is an incredibly broad church, ranging from physical impairments to learning difficulties and those with mental health issues. The vast range of challenges faced by disabled students, does mean it is difficult to gauge how effectively students are performing at various stages through their academic life.

The OfS reports that disabled students are doing less well than non-disabled when it comes to continuing their course, attainment or progressing onto skilled jobs. But these disparities can become even more acute in relation to certain disabilities. For example, data taken from student surveys in 2016 reveals that undergraduates with mental health issues have lowest continuation rate.

Furthermore, of the disabled students who graduated in 2016-2017 with a social or communication impairment, only 61.8% of them progressed into skilled work or postgraduate study compared with 73.3% of non-disabled peers.

- Collecting quality of that data to help assess the progress of disabled students.

Data collection remains a considerable issue as many students still don’t disclose whether they have a disability. This, as the OfS identifies, may be due to the fact they still feel there is a social stigma attached to having a disability or because they do not identify as disabled. This means there is a good chance that any data on which conclusions are drawn is at risk of being distorted.

The answer is to create simple, less laborious ways of data collection. However, this should also be coupled with a more accurate way of collating data. For example, the OfS notes that some methods of surveying student populations have a tendency of grouping disabilities together. Data can only be of any real use if it is as detailed and as accurate as possible.

Adoption of the social model – By no means the bare minimum, but still room for improvement

The OfS report does identify that universities have gone a considerable way to a moving towards a social model of disability which promises genuine inclusivity for disabled students whatever their impairment. The report points to the fact that 100% of universities now make course materials available online whilst 95% offer alternative assessment methods.

However, only 8% of universities record all lectures and there are still disparities in relation to the types of facilities available. Another area which requires attention is student accommodation. Living arrangements for disabled students vary greatly from provider to provider and yet this is one of the most important facets of student life.

The OfS report concludes that whilst much has been done, there are still notable areas for improvement where progress has been disjointed and patchy. It is hoped that the good work of the OfS, DSC and TASO will continue in narrowing these gaps and making sure universities are a place where disabled students can reach their full potential.

Writer’s closing comments – a social model of disability in the workplace?

On the whole, I found the OfS report to be encouraging. There is clearly work to be done and still some way to go before universities fully embrace the social model, but the feeling is that we are getting there. It also seems to me that adopting the social model is the only real way of ensuring genuine inclusivity.

Only by bringing about this cultural shift in attitudes towards disability can disabled student feel not only a true part of the education system, but a part of society as a whole.

Indeed, the OfS report prompted me to think that the social model of disability should be encouraged in the workplace. Shouldn’t employer’s be required to engender the kind of environment where their disabled colleagues can flourish? Wouldn’t employers benefit from attracting more disabled workers into their staff community?

If universities are striving to adopt the social model, why should we stop there…?