Disability in children’s books is not a new phenomenon. That said, it is something which is still ignored by most contemporary mainstream authors. This was not always the case. Looking back through literary history, disabled characters in children’s book were more common. Disability is a complex and sensitive area to write about in any children’s book. So perhaps it is not so surprising, disabled characters are noticeably absent from children’s literature. Furthermore, there may be a perception that disability is not really something that most children would identify with. Disabled people, despite social progress and protection from the legislature, remain very much on the periphery of society. It is a topic which many still find difficult to discuss.

Aims of this blog

This essay discusses disability in children’s literature. It examines certain children’s books with disabled characters and explores how such characters have been represented historically. It also observes how disabled characters in literature are represented now. Finally, this piece suggests ways in which we might encourage children’s books to be more inclusive where disability is concerned.

A number of recent articles have noted the lack of disabled characters in children’s literature. They observed that the disabled characters in children’s books who do exist appear, at best, rather bland and underdeveloped, at worst misleading. They also highlighted the tendency to pen stereotypical characters who are defined by their disabilities in rather clichéd and patronising ways.

As a person who grew up with a disability, I believe that introducing disability in children’s books plays an important part in ensuring disabled people enjoy representation through literature. This in turn, spreads disability awareness and assists in the integration of disabled people into society. However, the subject of disability and children’s books needs to be approached with care.

Children’s literature should reflect society and its inherent cultural diversity as accurately as possible. Nevertheless, children’s books which mechanically introduce characters with disabilities in order to meet some kind of literary quota will fail to achieve any positive impact. There is no doubt that children’s literature has a role to play in making sure that disability does not go ignored. However, the subject of disability in children’s books is a sensitive one.

Disability in children’s books – the legacy of Tiny Tim

The late 19th Century and early 20th Century, offered many books featuring disabled children. Charles Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol’ saw the creation of one of literature’s most famous disabled characters, Tiny Tim. At the time this book was written, disability was commonplace. Whether due to malnutrition or ill health, disability was far more the fabric of society, especially among the poor. Small surprise, therefore, that it found expression in the works of Dickens and other social commentators.

The wheelchair-bound Clara in ‘Heidi’, a product of Johanna Spyri, was another memorable example of how the theme of disability in children’s books was introduced. Further illustrations of disability in literature include Susan Coolridge’s ‘What Katy Did’, ‘The Secret Garden’ by Frances Hodgson Burnett and ‘Pollyanna’ by Eleanor Porter.

Authors were not afraid to approach the subject of disabled children in literature in those times. That said, disability was far more of a common occurrence. Polio, for instance, affected far more infants that it does today often leaving the patient permanently crippled, whilst battles such as the first and second World Wars resulted in millions of injuries and created a whole generation of disabled people.

However, this is not to say that authors were not guilty of inaccurate stereotyping where disability was concerned. There are those who argue disabled characters were often misrepresented. All too often, states Professor Ann Dowker1 of Oxford University such disabled characters could appear rather ‘two-dimensional’.

They often found themselves pigeonholed as villains or ‘saintly invalids’ – a categorisation which was as simple as it was misguiding. The cause of their disabilities was often left unexplained, notes Dowker. Such a lack of medical specificity could result in a stylised treatment of disability. In other words, disability in children’s books was often used in literature as a tool to invoke feelings of pity or fear.

Nevertheless, some children’s books written at that time, did contain far more developed disabled personalities. Dowker cites novels such as ‘Fifth Form at St Dominic’s’ by Talbot Baines Reed and ‘Mia and Charlie’ by Annie Keary. Both children’s books contained disabled characters of far greater complexity than the other more stereotypical figures featured in the novels of Dickens and Burnett.

Despite this long literary history, today, disabled characters in children’s books are in the minority. Perhaps this has come about due to the progress made by medical science. Disabilities are not as common as they once were. Childhood illnesses such as polio and measles, which could result in severe deformity or brain damage have been all but eradicated.

Furthermore, disabilities are now diagnosed with far more accuracy than ever before. A hundred and fifty years ago, so little was understood about the various forms of disability that they would often be incorrectly identified. Those with mild cerebral palsy would be termed ‘lame’, whilst others with a more serious form of the condition, may well have been incarcerated in some form of mental institution.

Nevertheless, although we benefit from a far greater understanding of the various disabilities, physical and otherwise, it seems disability has faded from the modern literary landscape. JK Rowling’s ‘Harry Potter’ series barely contained any reference to disability, whilst the never-ending torrent of teen vampire literature is almost completely silent on the subject. Could it be that modern authors simply don’t feel sufficiently knowledgeable to accurately write about a disabled character? Possibly. It would be a very daring (or foolish) writer who chose to tackle a given disability without having had some form of direct experience with the condition or without having researched the topic in great detail.

Disabled characters as a means of reassurance

One of the main arguments, which is put forward in favour of disabled characters in children’s books, is that they enable disabled children to identify with such characters. This, in turn offers them a sense of re-assurance, whilst also raising disability awareness amongst able bodied children and educating them about people’s differences.

Children’s books, which contain disabled characters may well serve to introduce able bodied children to disability. Nevertheless, I am not so sure that disabled children themselves would seek out such a novel. On the contrary, I would suggest the converse is far more likely.

For me, children’s books were all about escapism and adventure. I never searched for a book which contained disabled characters in order to feel some comfort or sense of identity. My mother bought a copy of ‘Heidi’ for me when I was young. I enjoyed the book immensely, yet I never regarded Clara as an individual with whom I shared any common ground. Perhaps this is because, as a young child I did not see myself as disabled. I chose stories purely based on the attractiveness of the cover and whether or not, on reading the first page, the author had managed to grab my attention.

Children’s books which contain positive disabled characters may well offer comfort to the disabled reader. However, I would hazard a guess that it is the parents of these disabled children who crave this reassurance, rather than the children themselves.

Disabled children will continue to judge books on exciting content and the ability of the author to spin a convincing yarn. Whether the characters are able bodied or not is of little significance for most disabled children. That is not to say that literature has no role to play in educating children about disability.

Children’s books are often one of the best ways to learn about things which may not be experienced within a child’s usual family unit. Therefore, its importance in educating people about disability and raising disability awareness should never be underestimated.

Disability in children’s books – the modern writer

Cathy Reay, recently commented that children’s books can give a distorted image of disability.2 From Frances Burnett’s ‘The Secret Garden’ to ‘The Subtle Knife’ by Philip Pullman, she identifies authors who still paint a negative, even shameful image of disability.

Reay observes that far more has to be done to introduce disabled characters in children’s literature. To this end, she writes that “until hugely successful authors like Jacqueline Wilson and J K Rowling step up and take disability on board, it might be difficult to get children to read anything other than stories about vampires and wizards.”

In a recent initiative, Scope, the UK’s leading children’s disability charity tried to do just that. The organisation set about encouraging authors and illustrators to write new children’s books with disabled characters through its ‘In The Picture’3 campaign. To assist, the charity set out a list of guidelines:

1. Books should be created with all children in mind, for all children to share and enjoy.

2. The point is not that disabled children should be the prime focus of stories or pictures: simply they should be there, a natural feature of every child’s landscape.

3. Images of disability should be the norm, in the same way as images of different ethnicities are now the norm.

4. Images of disabled children should be used casually or incidentally, so that disabled children are portrayed playing and doing things alongside their non-disabled peers.

5. Disabled children should be portrayed as ordinary – and as complex – as other children, not one-dimensional.

6. Disabled children are equals and should be portrayed as equals – giving as well as receiving.

7. Disabled children should not be portrayed as objects of curiosity, sensationalised or endowed with superhuman attributes.

8. Stories should not have ‘happy ever after’ plots that make the child’s attitude the problem.

9. It is society’s barriers that can keep disabled children from living full lives.

10. We should always remember that disabled children are children first and like all children have hopes and aspirations just like their peers.

11. The lives of all children will be enriched by disabled children being ‘in the picture’ – it will help build understanding for all children and adults.

Scope’s aim was to encourage the inclusion of disabled characters in children’s books in a way that treats disability as a mere characteristic, such as wearing glasses, or being black. As they state in their third guideline, “images of disability should be the norm, in the same way as images of different ethnicities are now the norm.”

Children’s books with disabled characters – a literary exercise?

There is much to be applauded here. Children’s books should contain disabled characters, just as they contain children from other ethnicities. It is important that able bodied children see disability as part of everyday culture. But whilst it would be an improvement to see disability featuring more prominently in children’s books, I have a real concern that should popular authors attempt to write about something which they know little or nothing about, the effect could be counter productive.

The JK Rowlings and Stephanie Meyers of this world may be able to do much by introducing disabled characters into their books at one level. On the other hand, the people best placed to write on this subject are disabled people themselves. In my opinion, there is a wealth of untapped material which has yet to be written by disabled children’s authors around the world.

I fully appreciate what Scope is trying to achieve, but these guidelines could be regarded, in part, as misleading. In reference to guidelines 8 and 9 above, I heartily agree that “happy ever after plots” which centre around the cure of a given disability are definitely to be avoided.

That said, a disabled child’s attitude to their own disability may well be a very real and powerful issue in the story. It is not always society’s barriers that can keep disabled children from living full lives. Sometimes it is the negative attitudes of the disabled people themselves that prevent them from achieving their potential.

Furthermore, it should still be realised that disabled children are different from their able-bodied peers. They are not the same as ‘normal’ children. Being disabled is a very complex and personal attribute, which affects every disabled child differently, more so than colour or creed. Able bodied children should, of course, realise that disability is nothing to be feared or shunned, but we can hardly suggest the image of the disabled child is the same as a child from an ethnic minority for example.

Can children’s books with disabled characters ever be cool?!

Apart from a few exceptions, books about disability generally never make the bestseller lists. This is hardly surprising. Authors prefer to pen stories about subjects on which they have some experience. Disability is a difficult subject on which to write. Unless the narrator has true experience of the issues, thoughts and emotions of living with a particular disability, there is a real danger that a story will appear false and awkward. At best it may seem implausible, at worst, patronising.

Another reason is that rightly or wrongly, disability in children’s books just isn’t ‘cool’. Modern mainstream literature just does not seem to favour disabled characters. The idea that the hero of a story might have a debilitating condition or permanent disfigurement just does not seem to ‘fit’. Literary agents want books that are zingy, fun and interesting (quite rightly too!) and the cold hard truth is that disability in children’s literature, isn’t regarded as an attractive sell. In fact, I would almost go so far as to claim that children’s books with disabled characters are taboo.

But it doesn’t have to be that way. For me, stories involving disability are fascinating. Disabled people often have to grapple with and overcome powerful issues which go to the very core of their being. How can stories based on such emotions do anything but entice the reader?

I’m not too concerned whether popular authors start to write more children’s books with disabled characters. I’d much prefer to see more books written by disabled people, inviting us into their worlds and sharing their hopes and fears. Apart from anything else, disabled people have such a different perspective on the world than able-bodied people. Their personalities are shaped by an entirely different set of physical and psychological challenges. How can such a unique experience of the world fail to be of interest to the voracious reader?

Fortunately, there is growing evidence to suggest that books with disabled characters are beginning to develop a bit of a following of their own. I recently came across an interesting thread on the literary social networking site ‘Goodreads’ called ‘Children’s Books with Disabled Characters’. This thread has now been running for over three years and lists a number of novels where disability features prominently. Little by little the literary world seems to be developing an appetite for books which explore this theme. Long may that continue.

My hope is that books about disability, written by disabled people, begin to enjoy the same amount of publicity and popularity as other books which have dealt with topics such as race and religion. Just as Zadie Smith was, at one time, the only book worth reading for the urban multicultural man or woman about town, it would be lovely to think that books involving disability might one day enjoy such popularity. The disabled community needs to find its ‘White Teeth’! Then and only then will literature’s attitudes to disability really change.

Children’s books should first and foremost entertain

However, when all said and done, for a book to achieve any of the aims above, it must first be successful and for that the criteria remains as constant as ever. First and foremost a book must be cable of moving the reader and capturing their interest. Until the novel achieves this, everything else is academic.

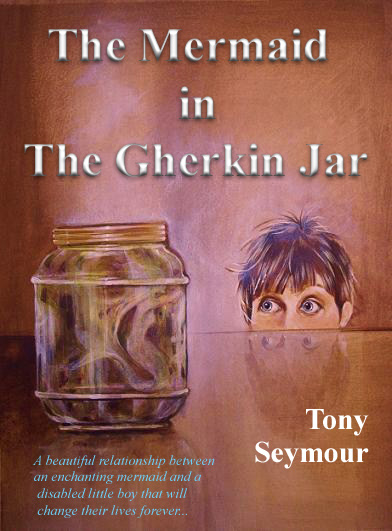

I did not write ‘The Mermaid in The Gherkin Jar’ because I felt a need to address some sort of literary imbalance with regard to disabled characters in children’s literature. Yes, the two main characters have disabilities which are central themes to the novel, but raising disability awareness was not the primary aim.

I wanted to explore the psychology of disability and the feelings which I experienced as a child growing up with cerebral palsy. But I wrote the story, principally because the characters felt real to me and because it contained all the magic and escapism I used to look for as a child.

I hope my book does well. I hope it raises disability awareness and teaches children and their parents about cerebral palsy, whilst unlocking some of the powerful feelings and emotions, which drive me and many other disabled people. But more than anything, I hope it entertains.

1 ‘The Treatment of Disability in 19th and Early 20th Century

Children’s Literature,’ Professor Ann Dowker, Dept of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford.

http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/843/1018

2 ‘Missing – disabled characters in children’s fiction,’ Cathy Reay

http://www.disabilitynow.org.uk/living/features/missing-disabled-characters-in-childrens-fiction

3 In The Picture – Scope

http://www.scope.org.uk/campaigns/inclusion-and-participation/disabled-children-books

Hi Tony,

Thank you for your post. I am looking forward to reading your book. I am a MA student in Special Education and am currently writing a paper on Childrens Literature and the Disability models. I have referenced you in my piece.

Best wishes,

Alison

Thanks Alison! Glad you liked the blog. Will definitely take a look at your paper. Sounds really interesting. Really appreciate you taking time out to comment on my website. It means a lot!