Eddie Redmayne recently received a Golden Globe and a good deal of well-deserved praise for his role as the young Stephen Hawking in James Marsh’s ‘The Theory of Everything’. The film charts the young physicist, who developed motor neurone disease (MND), whilst courting his first wife. It has already attracted critical acclaim around the world, notching up no less than ten BAFTA nominations and five Academy Awards nominations. However, it has not escaped criticism. Some have cited the film as yet another example where disabled actors have been overlooked in favour of their able-bodied counterparts. Is this true? Is playing a disabled character the equivalent of ‘blacking up’? Or a guaranteed way to secure a stash of accolades? Should disabled roles simply be the preserve of disabled actors?

Frances Ryan’s recent article in ‘The Guardian’ suggested that Eddie Redmayne’s Golden Globe winning performance of the disabled Professor Stephen Hawking was the equivalent to ‘blacking up’.

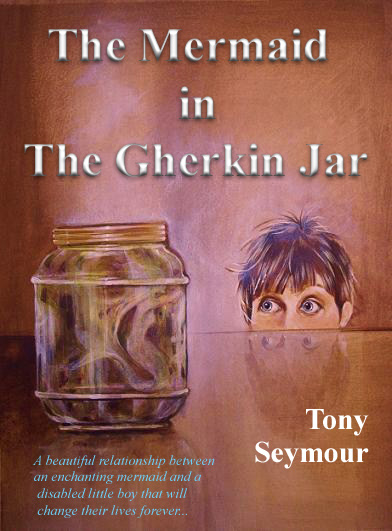

I took this and the other points made in the column very seriously. After all, as a disabled person myself and writer of ‘The Mermaid in The Gherkin Jar’, I wrestled with similar issues when working with Northern Rose in bringing the story to the stage. Christopher, the disabled little boy in the book, is currently played by an able-bodied actor and I still wonder what a disabled person might think of this, were he or she to see the full studio production at The Lowry Theatre in September 2015.

The current actor who plays Christopher in the stage adaptation of ‘The Mermaid in The Gherkin Jar’ is able-bodied. Is this to be seen as ‘cripping up’?

The reality of casting the stage production of ‘The Mermaid in the Gherkin Jar’ is perhaps similar to Eddie Redmayne’s role in ‘The Theory of Everything’. In the film, Redmayne must play both the able-bodied Stephen Hawking before his MND diagnosis as well as the increasingly crippled scientist, once the disease starts to take hold. Similarly, the actor playing Christopher in ‘The Mermaid in The Gherkin Jar’ must play able-bodied as well as disabled roles. Therefore the part of Christopher must be adopted by someone capable of slipping between disabled and non disabled personas.

I thought reading Ryan’s article might cause me to doubt this. On the contrary, it only served to assure me that disabled people are not the only ones capable of playing physically challenged parts.

A number of key points can be distilled from her column, which I will attempt to look at in turn:

1) An able-bodied actor taking on the persona of a disabled person is the equivalent of a white person wearing make-up to play a black person;

2) Playing a disabled character is a good way of securing an Oscar or some other such award;

3) Able bodied people feel more comfortable seeing disabled roles portrayed by able-bodied actors;

4) Giving disabled roles to able-bodied actors is robbing disabled actors of a role which is rightfully theirs, denying them the right of self representation and further perpetuating the exclusion of disabled actors from the stage; and

5) It is wrong for someone from a minority group being depicted by someone from a majority group for mass entertainment.

1) Is ‘cripping up’ the modern day equivalent of ‘blacking up’?

The first observation to make here is that Frances Ryan only seems concerned with physically disabled people. No mention is made of roles involving those with severe mental or behavioural problems. So, whilst it is acceptable for a mentally balanced person to play a manic depressive or paranoid schizophrenic, it is wrong to allow an able-bodied actor to portray a disabled character. Why? I’m not exactly sure. It seems to be an issue of perception and visual impact.

‘Blacking up’ in the 1920s – Al Jolson and Mae Clarke

Writing as a disabled person with mild cerebral palsy, I have read the multitude of comments which followed Frances Ryan’s article on ‘The Guardian’ website. I have also researched a host of other opinions held by writers and social commentators on the issue. As such, I am only too aware of how serious and sensitive this matter is and how some disabled people may feel offended by comments which they perceive as going to the core of who they are.

However, having thought hard on this point for a couple of days, I have come to the firm conclusion that I absolutely cannot agree that the act of so-called ‘cripping up’ is the equivalent of ‘blacking up’ for stage and screen (at least not in the way that Frances Ryan implies).

‘Blacking up’ as a derisive act of racism

The practice of white actors donning makeup to assume the personas of black characters was widespread in the early 20th century where blacks were patronisingly perceived as simple, servile human beings or figures of comical derision. In other words, the roles perpetuated racism and the erroneous belief that black people or any ethnic minority for that matter, were somehow inferior to the white majority. Back then, society actively alienated and discriminated against black people.

But modern day ‘blacking up’ still occurs

As Ryan asserts, the kind of ‘blacking up’ that occurred all those years ago to poke fun and belittle black society has rightly stopped. But this is not to suggest that ‘blacking up’ does not happen at all to enable an actor to more accurately assume a role. Sir Ben Kingsley won an Oscar for his interpretation of Mahatama Ghandi in the 1982 film of the same name. Perhaps the fact that his father was Indian helped to silence any critics, though the Yorkshire-born actor still had to wear a considerable amount of make up for the role.

Sir Ben Kingsley as Ghandi in Lord Attenborough’s 1982 film of the same name. Should his role be considered as an outrageous example of ‘blacking up’?

To say that wearing make up to more accurately portray a role is an inexcusable act of bigotry seems rather exaggerated. The so called ‘blacking up’ which occurred in ‘Ghandi’ was not some racist act aimed at arrogantly excluding ethnic minorities from cinema, it was the result of the late Lord Attenborough’s desire to accurately depict one of the most famous freedom fighters of all time. In other words to make the Sir Ben Kingsley’s characterisation of Ghandi more convincing.

Eddie Redmayne was cast to play the brilliant physician because, like Sir Ben Kingsley, he is a talented actor with a proven track record. It is also apparent from the screen shots that his physicality is very similar to the young professor. He is a good ‘fit’ and believable in the role.

For these reasons the so called ‘cripping’ up of actors to play roles such as Stephen Hawking in ‘The Theory of Everything’ or Christie Bowne in ‘My Left Foot’ is little if anything to do with the kind of motives behind ‘blacking up’ which occurred so many years ago. It is in fact, more as a result of the actor’s intention to transform him or herself into that role, in the same way as he or she might wear a befitting costume.

2) The use of disability to guarantee an award

There are many occasions where playing a physically disabled person has led to an award. The examples are numerous. However, there is a danger that pointing this out time and again begins to sound just a little cynical, if not bitter.

I don’t know the criteria on which awards are presented, but I should guess they run a little deeper than an actor faking a limp or a stumbling gait. One thing is for certain, approaching topics such as disability is almost certainly quite a challenge, not just for the actor, but for the director and producers involved.

It must be the case that, in making a film such as ‘The Theory of Everything’, those involved wanted to be as thorough as possible in understanding the nature of Hawking’s disease. That probably explains the months of research conducted by Eddie Redmayne. Amongst other things, he studied MND and visited patients who were suffering the affliction. Before even attempting to mimic the physical symptoms, a great deal of time was spent understanding what it was to have the disease. Surely that difficult challenge, if executed well, is worth an Oscar.

To turn the argument on its head, are we saying that a great actor, who happened to have MND, would stand no chance of an award were they to play a young Stephen Hawking with the same disease?

I would agree that many actors have certainly won awards on the back of portraying disabled characters, but this is not because it is an easy cop out. It is because it is a tough challenge where the able bodied actor must really be at the top of their game to carry it off successfully. If they do, it is only right that they receive the acclaim they deserve.

3) Able bodied people feel more comfortable seeing disabled roles portrayed by able-bodied actors

I agree with Frances Ryan here. Hand on heart, there are times when I have found it hard speaking with people with severe physical impairments. It’s a devastating reality with which we’d rather not deal, so I can understand how it’s more reassuring to see an able-bodied actor walk away from a disabled part. Nobody likes to face a harsh truth. That does not mean we should not confront it at all, of course. Nevertheless, there are numerous films, where the use of an actor and the illusion of make-believe elicits a sense of relief such as seeing brutal re-enacted scenes of the holocaust or apartheid.

4) Giving disabled roles to able-bodied actors is robbing disabled actors of a role which is rightfully theirs

I have already touched on the fact that there is more to playing a physically disabled character than simply ’cripping up’. Pretending to have the same physical handicap is not enough. The actor must be convincing. He or she must engage with the audience so that they buy into the story. In other words they must draw on their subtle skills as actors to cast the magic that is necessary to make a tale genuine. If all that is needed to play a character with a given physical disability is personal experience of the same handicap, then this would give a very narrow, almost blinkered view of what it is to be an actor.

A shortage of disabled actors

Furthermore, one cannot ignore the financial perspective. Producers must make a film or theatre performance pay and so, like it or not, they require personalities who attract the crowds. To be fair, this is something that Frances Ryan readily understands.

But the criticism that able-bodied actors automatically win disabled roles over and above their disabled bodied counterparts also seems to imply that there is a rich seam of well known disabled talent just waiting to fill any role depicting physical impairment. This is simply not true.

The only agency which focuses on representing disabled actors in the UK, of which I am aware, is the VisABLE Model Agency run by Louise Dyson. The agency represents well known disabled actors such as Colin Young who played a key role in the BBC’s ‘Call The Midwife’. VisABLE is an excellent resource for any casting director looking to hire a disabled actor, but that does not mean it is always easy to find someone for a specific role.

For instance, the role of Christopher in the physical theatre production of ‘The Mermaid in The Gherkin Jar’ would require someone with cerebral palsy who is also capable of performing the other able-bodied elements of the piece. As someone with Christopher’s condition, I can assure the reader that this is something which is really rather difficult.

RJ Mitte – one of the painfully few disabled actors (with mild cerebral palsy) who has built a mainstream career in show business. Long may that career flourish.

On this point, one actor I did have in mind for the role of Christopher was RJ Mitte, star of the hugely successful US series, ‘Breaking Bad’. In many ways he would be absolutely perfect, but I doubt the production company could afford his fee. Not at the moment anyway! Furthermore, there is no guarantee that such an actor would want to audition for the part. An actor’s career flourishes as his roles become more and more varied. Would any actor with a disability really be content being the ‘go-to’ man or woman for any piece involving physical impairment. I think not.

The assumption that there is a multitude of eager actors who are missing out on plum disabled roles played by able bodied, award-hungry actors is misleading. These roles are actually relatively few and far between and arguably not enough to sustain any acting career.

Why is disability so precious?

Perhaps the biggest point that Frances Ryan made which I found difficult to agree with was her comment that seeing an able-bodied person assuming a disabled persona is “for many people in the audience” the same as “ watching another person fake their identity.”

The obvious point here is that faking another identity is exactly what acting is all about. Moreover, why shouldn’t able-bodied actors play disabled roles? Are these parts so sacred to suggest that no able-bodied person could possibly interpret them accurately? I have watched a number of films depicting disability and I have never felt that my own identity as a disabled person is being faked. The idea is frankly absurd.

Mental disability has often been portrayed by healthy actors without the likes of Mencap taking to the street claiming the collective identity of their membership has somehow been faked. What is the real difference with physical disability? I just can’t see it.

5) It is wrong for the story of someone from a minority to be depicted by a member of the dominant group for mass entertainment.

This statement would be beyond debate should any theatrical role be used by a ‘dominant group’ to somehow belittle or undermine a minority. But, as I have already mentioned, this was not the case in roles such as ‘Ghandi’. Far from being an insulting portrayal of the Indian revolutionary, Sir Ben Kingley’s interpretation was arguably a powerful and insightful piece of acting, worthy of great praise.

Similarly, Eddie Redmayne’s portrayal of Stephen Hawking and Daniel Day Lewis’s role in ‘My Left Foot’, to name but two, could hardly be argued in terms of a majority group capitalising on a minority group for the sake of entertainment. I am personally thankful that actors and directors see these stories as so important that they must be told and I am happy to see them gain further publicity through their connection with famous faces.

The harsh reality of disability in film

There was a time when there were hardly any black actors in cinema, because the barriers towards them were so great. Over time the barriers to such actors broke down and more and more black artists as well as players from other ethnic minorities emerged.

The same will happen, to an extent, with disabled actors and stars like RJ Mitte and Colin Young will, no doubt, lead the way. However they will always be few and far between. There is a very real and harsh truth to face – disabled people will always exist in far fewer numbers comparative to other minority groups, and the nature of having a disability will make it more difficult to play a wide variety of roles resulting in the majority of them losing out on blockbuster scripts.

An actor with severe cerebral palsy or MS might be able to play the role of Stephen Hawking in a wheelchair, but would find it impossible to pass off an able bodied Cambridge student before MND took hold. An actor such as RJ Mitte could have perhaps been a good call as an alternative for Eddie Redmayne, though bizarrely he would have to ‘crip down’ for the first part of the film and ‘crip up’ for the latter part. Is there any real difference? Also, as previously discussed, there is more to playing any role than simply being able to mimic the physical attributes of the character.

Similarly, casting Christopher for ‘The Mermaid in The Gherkin Jar’ is not as simple as hiring the first actor one can find with cerebral palsy or a similar condition. After all, CP itself is a broad church that affects different people in different ways. Colin Young, (although I thought about it) would have not been suitable as he wouldn’t be able to execute the more physically demanding able-bodied parts of the piece. This is a real shame as I think other aspects of his physicality would have been an excellent fit. Perhaps there are other actors out there with a milder form of cerebral palsy, but would they have had the same facial and physical characteristics as our current cast member?

The danger here is that in trying to use a disabled actor, there is the very real danger that the piece may alter in a way that was not truly intended. This, as a writer, I will always resist. Furthermore, and I may well be lambasted for making this point, if we focus on the disability itself too closely, there is actually the real risk that the piece becomes just about that – disability.

Conclusion

At first blush, Frances Ryan’s article in the Guardian makes some strong points, but this is only because they appeal to our sense of outrage by hooking into emotive topics like racism. In reality, there is little in her article that holds water.

I’ve dealt with disability all my life and can honestly say I have never felt offended when an actor receives an award for ‘cripping up’. Nor have I felt anger that by casting an able bodied person, I have somehow lost my right to self expression. On the other hand I would feel far more disappointed if I watched a film that failed to deliver simply because of some misguided act of ‘positive discrimination’.

Don’t get me wrong, I would like to see more disabled actors in film. I want to see more talent agencies like VisABLE introducing actors into theatre casts and onto film sets. People need to see disability represented on TV and in the cinema as general roles. I can even see some disabled actors taking on far bigger parts.

But the reality of it is that those best suited to developing a mainstream career in entertainment are those at the periphery of disability, such as RJ Mitte who can keep their symptoms under control. This in turn allows them to play a wider variety of roles even perhaps able-bodied parts. Having said that, the irony is that I doubt that any such individual would wish to base their career entirely on roles made possible because of their disability.

Thanks. A very thoughtful, balanced and well written piece. But sadly there are still examples of lazy casting, arising from concerns about production schedules and costs and from low expectations of available actors with disabilities. For example, this week’s well written, well acted two part episode of “Doctors” BBC1 included two strong roles portraying men with learning disabilities, but acted by non-learning disabled actors. The acting was convincing but could have been equally or more so had learning disabled actors been cast. There are a number of trained and experienced actors out there who could have handled these roles. Some graduates of the excellent Mind the Gap/ Mountview training course for actors with a learning disability. Opportunities for them to work are few and far between, despite the best efforts of pioneers like Louise Dyson. This is partly about casting but more about the absence of bold commissioning and writing. “Doctors” has a relatively good track record of casting disabled actors. It is a pity that they felt unable to trust any of them to play either of these challenging roles. Opportunity lost all round on this occasion.